By

Syed T. Ahmed, Kudakwashe J. Chipunza and Sweta C. Saxena

Money makes the world go around, as they say. Conversely, the world stops if you do not have that resource. This is true for half of the world’s population who are women. Despite signing the Maya Declaration that aims to reduce poverty and ensure financial stability for the benefit of all and despite the goal of financial inclusion cutting through eight of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, women are excluded from enjoying its benefits.[1] Even with 75 per cent of the global mobile money account ownership in Sub-Saharan Africa[2], this has not translated to increased financial resilience and financial inclusion among women across the region.[3]

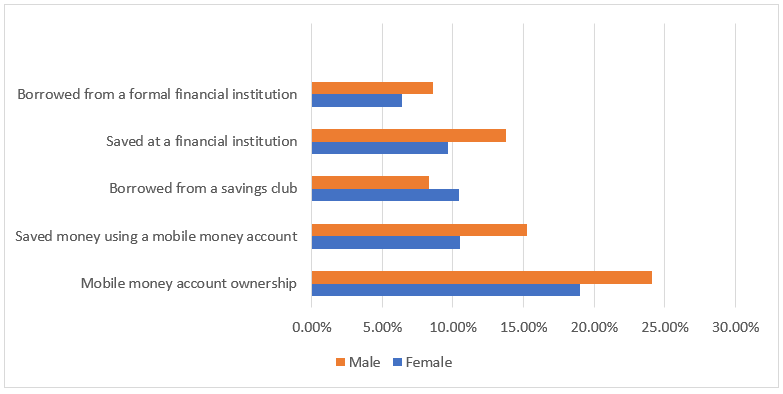

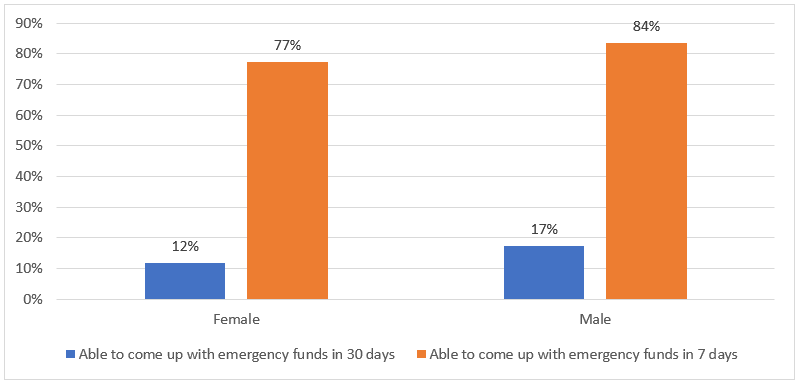

Women’s financial prospects are doomed, or so some would say, once you begin to interrogate the data available in the 2021 World Bank’s Global Findex dataset (Figure 2). Relative to their male counterparts, women struggle to raise sufficient liquidity to cover monthly expenses and bills, and fewer females can raise emergency funds when needed, impacting their financial resilience.

Liquidity and trust in times of turmoil

The challenges holding women back from financial resilience and excluding them financially are many. In Africa, 67 per cent of men aged 15 years and above are employed relative to 50 per cent of women. This disparity in employment across genders could partially explain why fewer women can save or borrow in formal financial systems, especially when savings are considered a vehicle for financial inclusion.[4] Instead, women resort to informal channels such as saving groups. However, these trust-based financial institutions such as saving groups, which more women in Africa rely on, might have limited effectiveness in providing liquidity when there is a covariate shock where all group members decide to simultaneously withdraw from the fund.

Literacy and choice during cycles of calm

The exclusion of women in formal financial systems is worsened by low financial literacy rates, which not only limit their effective participation in financial markets but also contribute to poor money management and short-sighted financial decision-making that makes them vulnerable to adverse shocks. Moreover, financial products are not necessarily adapted to women’s unique experiences with money matters, including literacy, income, or even behavioural attributes, such as propensity to risk or likelihood of saving, for example. The failure to accommodate gender experiences in the design of financial products and services limits women’s inclusion in the formal financial system and their ability to absorb financial shocks.

Addressing the structural barriers to building women’s financial resilience

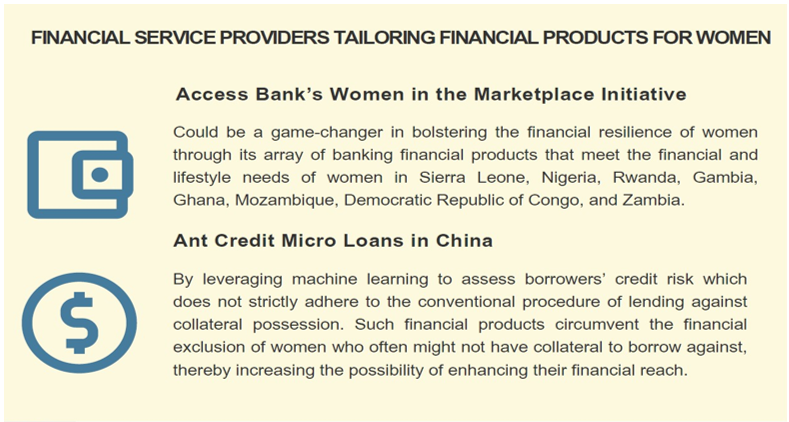

To create a financially inclusive environment that bolsters financial resilience, several considerations need to be made. The fact that most women are still reliant on informal financial services, owing to reasons such as low labour market participation and education, financial service providers in Africa should introduce innovative financial products that are tailored to the realities of women which, in turn, could reduce their vulnerability to adverse shocks. In addition, regulators should also ensure that administrative procedures, such as due diligence regarding client profiling, are not based on biased assumptions where women are disadvantaged due to lack of collateral or credit history. The box below highlights examples of service providers that have tailored their financial products to accommodate women.[5]

Along with such initiatives, it is imperative that the private sector, in the form of banks, financial institutions, and emerging financial technology companies, contribute to the financial acumen of their clients, as they play a central role in providing consumer protection and have a de facto responsibility for their financial inclusion. Therefore, it is incumbent to go beyond providing basic access to financial products and services and embedding financial knowledge in their service delivery. This would be pertinent insofar as equipping women to make informed decisions on financial matters which, in turn, improves their financial resilience.

Conclusion

While Africa has made significant strides in improving access to basic financial products and services among women, driven by the ubiquitous adoption of mobile money and digital finance platforms, this has not translated to improving their economic prospects. To effectively enhance the financial resilience of women in Africa, financial inclusion initiatives should be anchored on gender-sensitive regulatory frameworks and financial systems. To this end, a concerted effort between behavioural finance researchers, gender experts, the private sector and policymakers could help in creating a business case for gender-specific financial products that build the financial resilience of women. If this is properly administered, managed, and regulated, women’s financial prospects could improve by leaps and bounds.

[1] The Maya Declaration is detailed on the following link: https://www.afi-global.org/sites/default/files/publications/afi_maya_quick_guide_withoutannex_i_and_ii.pdf

[2] Global System for Mobile Communications (2024). The State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money 2024. Retrieved from https://www.gsma.com/sotir/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/GSMA-SOTIR-2024_Report.pdf

[3] Financial resilience is defined as the ability to absorb a shock or raise emergency funds (Demirguc-Kunt, Klapper, Singer & Ansar, 2022).

[4] ECA. (2022). African Women’s Report, Digital Finance Ecosystems: Pathways to Women’s Economic Empowerment in Africa. Retrieve from: https://repository.uneca.org/handle/10855/48741

[5] Access Bank. (2024). The “W” Initiative. Retrieved from https://www.accessbankplc.com/sustainable-banking/our-community-investment/the-w-initiative